Meet the Bajau Laut, The So-Called “Sea Nomads” – Inspiration for the Characters of James Cameron’s Avatar 2 Film

Hailing from the southwestern islands of The Philippines in the Sulu Sea and beyond, the Bajau Laut and a related ethnic group called the Sama (sometimes grouped together and called the “Sama-Bajau”) are a people found across Southeast Asia with a uniquely aquatic lifestyle. There are approximately half a million Sama-Bajau people living on land and within the territorial waters of The Philippines alone.

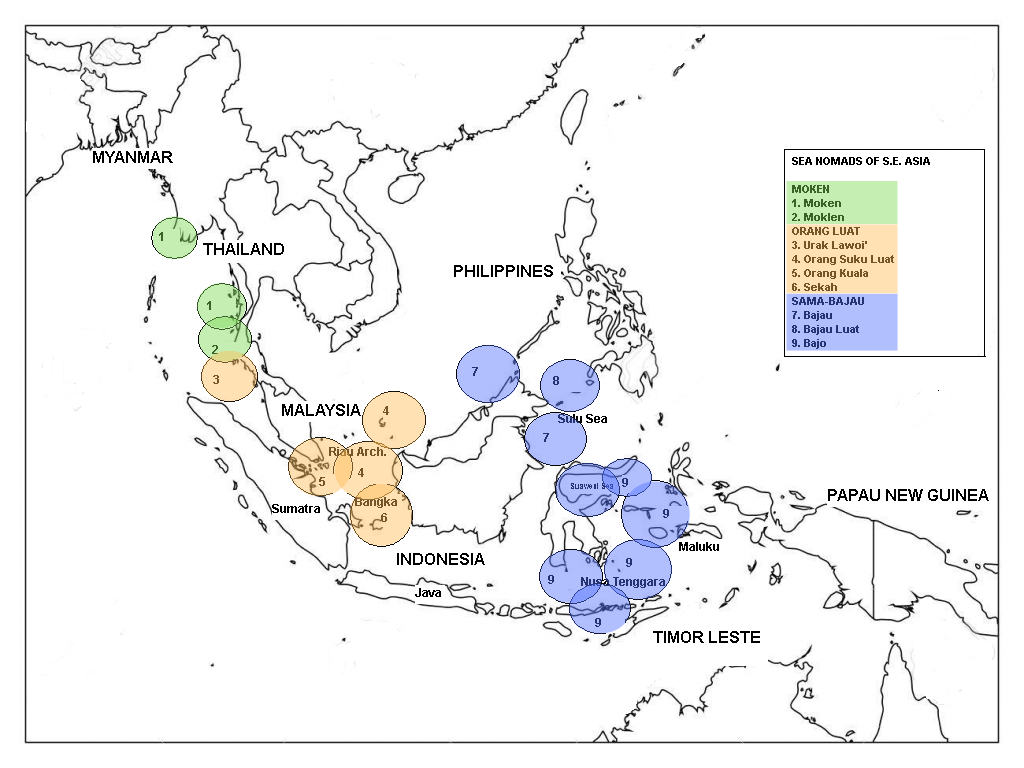

Along with the Moken and the Orang Laut, these three related people groups comprise the so-called “Sea Nomads” that are spread across several thousand kilometers of ocean, from Malaysia, to Indonesia, Brunei to Myanmar and The Philippines, with approximately 1.4 million members of the aforementioned people groups in total.

The Bajau Laut are emblematic of a people at home on the sea, so much so that even their very bodies have adapted over the millennia to spending much of their time in the water. Adults have been regularly recorded as being able to hold their breath for as long as thirteen minutes due to larger and more efficient spleens, higher hemoglobin content in their blood and are even able to focus their vision underwater, allowing them to see roughly twice as acutely as individuals hailing from continental Eurasia. These adaptations facilitate more time under water, more accurate identification of fish and camouflaged burrows on the seafloor where Mantis Prawn and other crustaceans hide.

While not truly nomadic (semi-nomadic is more accurate) and much less mobile than in the past, the Bajau Laut still engage in traditional practices of spear fishing and crustacean trapping, recently adding artisanal seaweed farming to their long list of aquatic skills.

Due to political and economic pressures on the Bajau Laut’s traditions, including the high cost of such basic commodities such as cooking oil, rice, diesel fuel and gasoline, some Bajau Laut have given up their traditional way of life and moved to big city Manila and other large cities hoping to earn a living there. Many of those same people have ended up in shanty towns and instead of fishing are begging on the streets. Their impressive skills are underappreciated by would-be urban employers and further gated by jobs that require formal education in a state approved school that a great many Bajau Laut do not have access to.

The Bajau Laut demonstrate the kind of innovation, adaptation and evolution that all societies that wish to endure possess. For the expertise they possess in making a living on the sea, there is probably no better group of people to guide eco tours, pilot fishing boat tours, operate an open-ocean fish farm or to demonstrate an environmentally sustainable seaweed farming business. There are many local dishes that now feature seaweeds in place of rice and minimize the use of expensive commodities such as rice and cooking oil, relying on what they can cultivate or catch themselves. Producing a unique, delicious and nutritious cuisine evidences what a community focused on self-reliance can accomplish.

There is much that can be learned, and the Bajau Laut are willing and eager to teach. Conceptualizing what a seasteading community might look like in the coming years is still at the theoretical stages in many respects, but for the Bajau Laut, it’s an everyday practice and the systems and methods they’ve developed to survive on the ocean have already endured for centuries. The Bajau Laut should be given the due respect they deserve for all they’ve accomplished.

Eviction, Deportation and Condemnation

Getting an accurate count of semi-nomadic people is understandably difficult, even more so if the goal for counting is to remove anyone who cannot prove their nationality and thus their right to remain in the country, both on land or within its territorial waters.

Even in the southern islands of Tawi Tawi where they comprise the bulk of the population, the Bajau Laut face discrimination from the government of The Philippines. Re-settling the Bajau Laut to permanent land-based camps has been proposed by the government in exchange for small stipends for living expenses in government supplied housing as an alternative to driving the Bajoa Laut out using more forceful means, but their continued presence as legal residents remains tenuous at best. No clear pathways to citizenship have been proposed, and outright removal remains on the table despite genetic, cultural and historic roots to The Philippines going back some 2000 to 3000 years.

While the government of The Philippines is trying to put on a good face and limit negative impacts to the Sama-Bajau to some degree, its efforts are wrongheaded. For their part, the sea-based Sama-Bajau want to farm the sea and fish using sustainable methods, not to toil over farmland which is becoming both more expensive and less available.

In addition to discrimination for following “the old ways,” Sama-Bajau often do not have the benefit of citizenship in ‘any’ country where they have traditionally travelled and more recently settled.

Across the islands of Indonesia, there are an estimated 345,000 Sama-Bajau. A further 460,000 live on the coast and in the waters around both western (continental) Malaysia and eastern Malaysia. An estimated 30,000 Sama-Bajau are found in Malaysia’s Sabah state in north-eastern Malaysia alone, but almost none of them hold citizenship in either country.

The large percentage of the population in Sabah state, Malaysia, that are ethnic Sama-Bajau even led to the state’s coat of arms being changed for a period of time to the kingfisher bird. The kingfisher is closely associated with the proud, largely self-sufficient Sama-Bajau people.

Thirty thousand estimated Sama-Bajau are believed to live in the waters of Myanmar, and an additional 12,000 can be found in the Sultanate of Brunei. As in the other countries where the Sama-Bajau can be found, they typically do not hold citizenship in their host countries.

Because the free movement of people between nations has become politically fraught, the pressure is on to force the Same-Bajau to become as sedentary as their land-bound neighbors and to go through a naturalization process to be permitted to call themselves nationals of that nation. Various strategies have been proposed to address the Sama-Bajau, as though they were ever really the problem. None of the solutions proposed so far are particularly workable, especially from the perspective of the Sama-Bajau people themselves who’d prefer to simply be left in peace.

For the Bajau Laut, the ocean is their territory and the sea akin to their native land. They wish to fish in their traditional waters using proven, sustainable methods, and to farm the seas and live on it, respecting it just as their forebears did.

The Bajau Laut’s traditional houseboats, the lepa, balutu and vinta, all of them long, lean, low affairs with variations in size and hull shape are typically occupied by a single family group with five or six family members, typically moving as a sea caravan with other family groups to share the load of fishing, cooking and childcare. Unfortunately, this kind of mobility and travelling in groups as a flotilla of houseboats has become increasingly rare with houseboats costing more to build and maintain than many Bajau Laut are able to afford. Living on a stilt home above the water, built from local materials, has become the de facto replacement for the once ubiquitous lepa.

This way of life, of moving with the seasons following fish migrations and attuned to the cycles of the sea predates both modern nation states and even many ancient empires, but this way of life now runs afoul of such notions as national territorial waters and state sovereignty. The ecological decline from ocean warming, acidification and the impacts this has had on already overfished fish stocks has further compounded the stresses on maintaining a lifestyle that depends heavily on free access to the sea.

The Bajau Laut don’t have the same notion of what defines a “country” as you or I might have, and it also doesn’t fit the definition that various international governance bodies rely on. These kinds of conflicts demand novel solutions, and one that many island nations that currently have the prerequisite of “a body of land” might soon face as sea levels continue to rise as a byproduct of higher surface water temperature leading to the land beneath their feet literally disappearing bit by bit.

In other words, helping to solve the problems facing the Bajau Laut might solve several more and all at the same time, solutions that could help lay the legal groundwork for recognition by the United Nations and other international governance bodies in the short to medium term for any and all micronations that seek to make their home on the ocean.

In the map below, we see the current range of the Sea Nomads, by group, including the Moken (upper left), the Orang Laut (lower center) and the Sama-Bajau (center right).

Nation-State Sovereignty and Disentitlement

Political pressures have risen sharply in recent years and have resulted in a ramp up of both policing and military patrols to curb or prevent foreign nationals from occupying national waters and harvesting fish from over-strained fisheries.

The governments of The Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia have stepped up enforcement at both the local and central government levels to remove non-citizens and send a clear message to all neighboring countries that long term occupation of their territorial waters is not equivalent to the rights of citizenship nor formalized intergovernmental agreements.

Both Indonesia and Malaysia have demolished the Bajau Lauts’ settlements with their distinctive raised stilt platform homes, even seizing their boats and any fish claimed to have been illegally caught. The sort of fishing that the Sama-Bajau engage in, by contrast with large commercial fishing fleets using much less eco-friendly methods, should be evaluated in how these practices actually impact fish populations. Despite obvious differences, the governments of these nations would seem to believe that a strong message needed to be sent and the Sama-Bajau drew the short straw on who would be made an example of to reach the intended audience, primarily the one seated in Beijing.

In Southeast Asia, competition for natural resources within the 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), particularly with China’s massive fishing fleet, has pushed small, indigenous groups like the Bajau Laut to the breaking point.

Forced out of their traditional seasonal fishing grounds and competing with large fishing vessels using destructive drag nets, gillnets and long-line fishing at industrial scale, some forward thinking Sama-Bajau have begun forming business cooperatives for seafarming, though the nationality issue is an omnipresent one for access to markets and puts significant barriers in place for where and how to set up prosperous enterprises.

Whereas the Bajau Laut were able to move at will from one island nation to another unfettered in the past, coast guard ships and armed naval vessels might now turn their boats away, or escort them from national waters under threat of arrest for any number of offenses, particularly for claims of engaging in illegal fishing.

Steps Towards Autonomy, Independence and Liberty: Possible Solutions

What solutions might be proposed that do a better job of resolving the competing interests at stake?

Fighting the uphill battle of finding acceptance for a semi-nomadic lifestyle with the governments of Southeast Asia might be a lost cause in an age where naval flotillas increasingly patrol nearby waters and run off or board any vessels deemed not to belong there. What alternatives might exist?

What if the Bajau Laut had floating villages away from the waters claimed by The Philippines, Malaysia, Myanmar, Brunei and Indonesia?

What if there was a fully aquatic, autonomous floating “hub” in international waters that allowed the Sama-Bajau and similar people groups to have the kind of autonomy and freedom that centuries ago was all but guaranteed?

Is the Sama-Bajau way of life a backward holdover from the past, or are they in fact at the cutting edge, destined for a renaissance as the kinds of skills they have developed over the centuries becomes exactly the kind of caché we need right now, making them the future teachers and partners of modern ocean-borne societies?

What sort of value might there be for having the Sama-Bajau continue to demonstrate a self-reliant seastead community operating on the high seas that trade what they grow for the things they need in a manner similar to what they’ve already been doing for centuries?

An oceanic marketplace and homestead in the waters of the Sulu Sea, replete with fish farms and seaweed farms, with all the basic necessities of life transplanted from shallow coastal lagoons to a floating platform away from land and far enough from the national waters of The Philippines and Malaysia would dismantle any argument that it infringes upon the sovereignty of those nations. Conversely, this will also mean that Malaysia, Myanmar, Indonesia, Brunei and The Philippines also cannot intrude on the sovereignty of a fledgling oceanic settlement’s ability to create its own rules and maintain its own distinct way of life.

Why Should TSI and the Community Consider Lending A Hand?

TSI defined the Eight Great Moral Imperatives of Seasteading as the pillars of its moral ethos, of which three appear to be particularly apropos to the current and near-term future circumstances of the Sama-Bajau and similar groups.

Restore the Oceans

Mariculture – growing fish in the open ocean, growing seaweeds, and other forms of aquaculture, practices which the Sama-Bajau are actively engaged in, could be expanded and new methods investigated to improve yields and reduce costs.

Live in Balance with Nature

A floating micro-nation, operating as a trade hub, will preserve the common features of Sama-Bajau culture, including its respect for the ocean and the demonstration of how to build a sustainable society operating in harmony with nature.

Live In Peace

All people deserve peace if their central tenant is to live and let live. The Sama-Bajau are a people of many different tribes, religions and beliefs, but they also demonstrate respect for the beliefs of others. This has allowed them to travel far and even settle in places among people with different cultures and languages. Until geopolitical pressure prompted formalized residency status, sedentary lifestyles or else forced displacement, the Sama-Bajao aren’t known to be provocateurs attempting to unseat the governments of the countries in which they live. A home on the sea, away from territorial waters, will allow the Sama-Bajau to live as they wish and live in peace.

The opportunity to form mutually beneficial agreements is time limited because of the nature of the crushing pressure being applied to ALL Sea Nomads at this time. While one can hope for better days for the Sama-Bajau, the reality is that it will probably get much worse before it gets any better.

In the coming decades, there will be fewer “Sea Nomads” to interview and learn from, and the extensive, irreplaceable knowledge they’ve been accumulating for centuries could be lost forever.

There’s something in it for seasteaders, as the legal framework that might be created to address the current and future needs of the Sea Nomads might also be highly beneficial to seasteaders when it comes to making a home on the high seas.

While the Bajau Laut might not be at risk of becoming extinct as a distinct ethnic group per se, their traditional oceanic way of life is in peril and will drive an increasingly large percentage of the Bajau Laut and similar people groups into becoming land-based, sedentary communities, eventually losing their impressive knowledge and skills in the process.

Can we afford to lose centuries of knowledge just as seastead projects are springing up on opposite sides of the globe, including one in proximity to the places the Bajau Laut call home in The Philippines?

Do we truly believe in liberty, at all times and for all people, or just some of the time, and only for some of the people?

Said another way, do we stand for the proposition that we should leave the undisputed experts at living in and on the sea to their fates?

They’ve succeeded in establishing centuries old trade networks, working with local governments on their own terms, built and maintained social bonds and preserved their cultural identity across the gulf of centuries. Should we stand idly by and watch as they are coerced into giving up their liberties in exchange for a bit of land or a place to sleep that doesn’t offend the current government, or do we stand with anyone who wishes to make their home on the seas, creating their own form of governance in keeping with their religious, cultural and personal worldviews?

The most important thing we could offer is to join in their efforts to gain legal recognition, and part of that recognition is demanding provisions to make it easier to certify and register a vessel, particularly those used by indigenous peoples whose closest connection with any government might be limited to the flagging registry that flags their houseboat or seastead. That would be a concession that could benefit us all.

When Should We Propose A Solution?

Time is of the essence. For less money than it costs to buy or seize land to build settlements with the usual assortment of basic services to encourage displaced Sea Nomads to join the “modern world,” floating platforms could be constructed and anchored in place to house people already accustomed to life on the water, and close enough to ancestral fishing grounds to continue their way of life without the spectre of rising tensions with local and national governments. Learning the ins and outs of the laws and regulations governing a vessel on the high seas is the largest impediment to their autonomy and independence, and so too is it a barrier to the seasteading community at large. Before the term was even coined, the Sama-Bajau and similar ocean-going people were already operating very much like seasteaders. The time is now to defend one of our own.